Hands in Pockets

A tale of two relaxations

The first time I went to a strip club, I was eighteen years old.

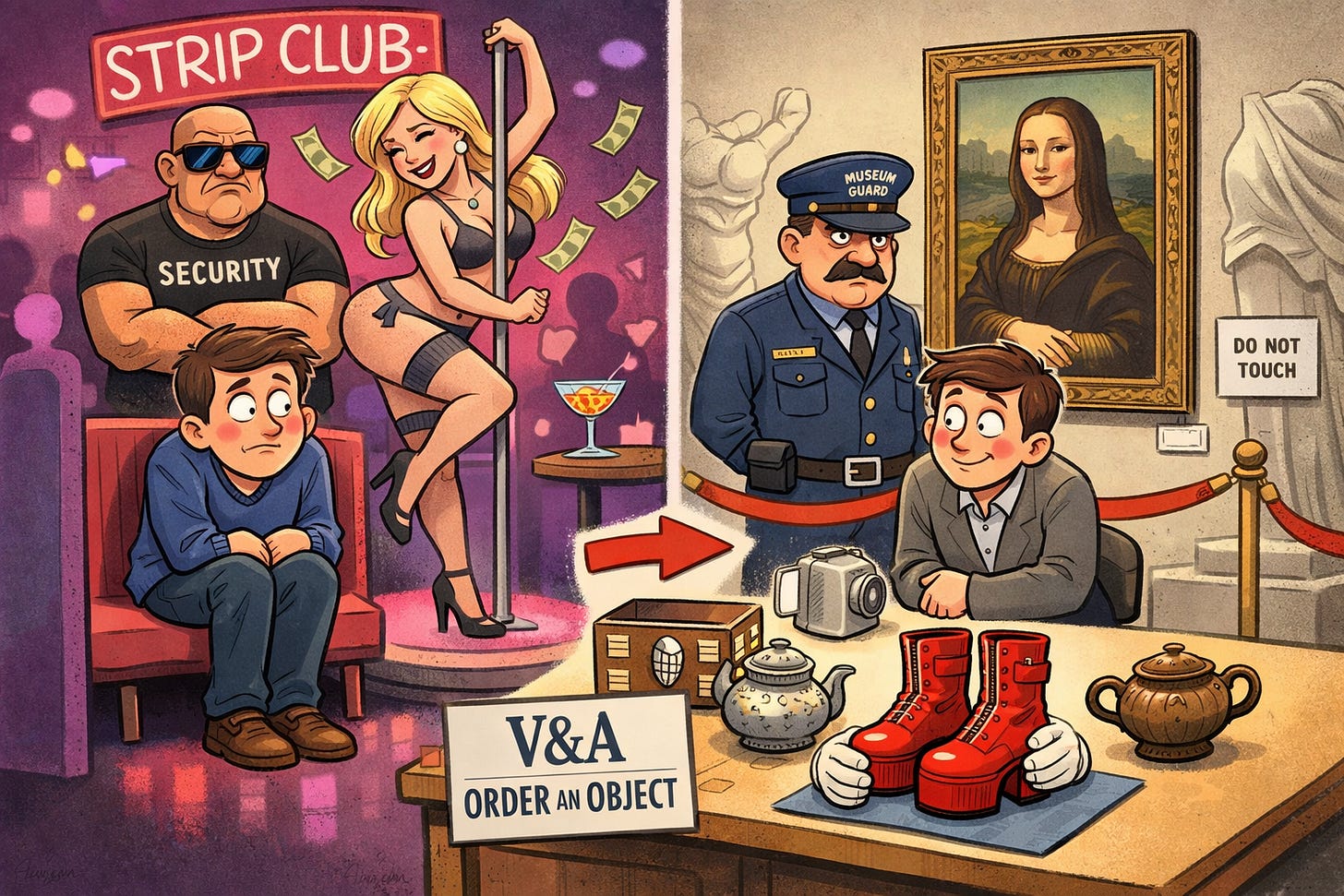

A friend from high school brought me to a place in Times Square. Before we went inside, he explained the rules. The girls could touch you. You could not touch them. If you did, the bouncers would beat you up and throw you out.

He bought me a lap dance. I was so afraid of breaking the rule that I sat on my hands the entire time. I hated every second of it.

Last year on vacation, walking through the Louvre in Paris, I noticed something odd. My hands were buried in my pockets or clasped behind my back. The entire time.

I realized I felt the same way I did in strip clubs. I was afraid, irrationally, that a guard might think I was tempted to touch the art. As if to signal my innocence, I kept my hands safely out of reach.

Since then, I’ve noticed I do this in every museum. Hands in pockets. Hands behind back. A bodily declaration of compliance.

Strip clubs and museums have more in common than we admit. Both are spaces where desire is assumed. Both are built around a central rule: look, but do not touch. And both enforce that rule through surveillance and shame.

They are designed not for the average person, but for the worst one.

Recently, I read about the Victoria & Albert Museum’s new East Storehouse in London. The V&A has more than 600,000 objects that rarely, if ever, go on display. Furniture, photographs, architectural fragments, David Bowie’s boots from the 1970s.

Instead of hiding them away, the museum has opened the storage itself to the public. Even more radical, they offer a service called “Order an Object.” According to this FT article, “almost everything is viewable via the Order an Object service, which allows anyone to call up five items and, in the company of a staff member, spend up to four hours with their chosen things. If the object isn’t too delicate or hazardous, you can touch it; if it’s not at all delicate, and it’s “meaningful” to the person (ie, a cabinetmaker might want to see how a particular joint works) they can handle it freely.”

This strikes me as both thrilling and terrifying.

Terrifying because it assumes something I’ve been trained not to believe: that people can be trusted. That proximity doesn’t inevitably lead to violation. That adults don’t need to sit on their hands to prove they are safe.

The V&A Storehouse rejects the strip club model of culture: The idea that desire must be tightly managed lest it become destructive. It replaces it with something older and rarer: respect.

I don’t know if I’m ready to put my hands on museum objects. I’ll probably still clasp them behind my back the first time I go.

But I like the idea of a world that doesn’t assume I’m one bad impulse away from being thrown out.

Digression

At 24, I was working in private equity and found myself on a research trip to Las Vegas with a senior partner and a vice president from my firm. We landed, dropped our bags at the Wynn Hotel, and before dinner, the partner announced that he wanted to go to a strip club. We got in a cab and told the driver to take us to the Spearmint Rhino.

In Las Vegas, cab drivers don’t just drive you to strip clubs, they sell you to them. The clubs pay a bounty for each customer delivered. Last I heard it could be as high as seventy-five dollars per person. Three guys in a taxi is worth $225 to the driver before the meter even starts.

If you’re smart, you negotiate. Tell the driver you’ll take the next cab unless he splits it with you. Some deny the bounty exists. Eventually, they all relent.

At the Rhino, we sat down at a good table. Within minutes, a woman came ove,r and the partner took her to the VIP room. A moment later, another woman did the same with the VP. I was left sitting alone, feeling deeply sheepish.

When the next dancer approached, who was the last person I would have picked in the place, I asked to go somewhere else. She led me to what was essentially a glorified bathroom stall with five-foot walls, open at the bottom, twenty feet from the main floor. I had to pay in advance: $100 for fifteen minutes on my credit card, plus an $18.95 processing fee.

Inside the stall, she asked if I wanted a dance. I did not. I just didn’t want to be the guy sitting alone at the table. I told her she could leave and that I only wanted to be able to peer over the wall.

The moment I saw the other two return, I bolted, rejoining them and pretending I’d had a great time.